How to collect your own data and overturn government policy

Back in 2014, the Home Office introduced the Right to Rent scheme, which requires landlords to inspect tenants’ passports to check they are not illegal immigrants.

But earlier this year, the High Court slapped a halt on plans to expand the scheme, finding that it caused landlords to discriminate against foreign tenants, and breached human rights law.

Amazingly, the High Court’s judgement was based not on official data (there was none), but on data collected by JCWI, a tiny charity. I’m writing about it because it’s a powerful and unusual example of a third party filling in missing numbers.

The judge also berated the Government for not collecting better data on whether passport checks actually deter illegal immigrants, in a tone I can only describe as judgemental:

The nail in the coffin of justification is that, on the evidence I have seen… the [Home Office] has put in place no reliable system for evaluating the efficacy of the Scheme.

So how does a 10-person charity collect better data than the Home Office, with all the powers of the state?

The Government’s numbers on Right to Rent: inadequate

Checking someone’s immigration status is complicated, and getting it wrong gets you 5 years of jail time. So the scheme obviously creates incentives to ignore tenants who look or sound foreign.

Many people pointed out this out the instant the scheme was proposed. So in its first pilot of the Right to Rent scheme, the Home Office ran a small study, staging a few hundred encounters with landlords, and comparing the response rates to white and BME tenants.

The results of the study found “no major differences in tenants’ access to accommodation”. And so the Home Office rolled out the scheme across England.

But how meaningful was the Government’s data?

How a charity filled in the gaps

The Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants (JCWI), a small charity, argued that the research was inadequate:

- The numbers were small and the data was oddly aggregated

- The methodology and aims of the study were unclear

- The scenarios used were limited and unrepresentative

I agree: I’ve read the Home Office study, and it’s essentially impossible to figure out how it was meant to work.

So JCWI collected its own data. It sent 1,800 emails to real rental adverts, from different ‘tenants’ with names like Colin, Harinder and Ramesh. It found clear evidence that landlords were less likely to reply to foreign-sounding names.

Then JCWI went to court.

What the courts said

At the High Court in March 2019, JCWI and others brought a Judicial Review of plans to expand the policy.

The judge agreed: the Home Office’s study was inadequate, and JCWI’s data showed that the scheme breached human rights law.

The written judgement notes that the Home Office collects no data on whether the Right to Rent scheme (which is still going in England) even works:

The Defendant was not collecting data that would allow it to measure discrimination resulting from the Scheme, the cost-effectiveness of the Scheme, whether the Scheme was resulting in migrants’ voluntarily leaving the UK or increasing the propensity of rogue landlords or the impact of the Scheme on agents and landlords.

As a reminder: the Home Office has an annual budget of £8.9 billion. JCWI has an annual budget of about £1 million. But still it somehow managed to collect better data.

Collecting data to force change

JCWI is the first to admit that its data isn’t perfect, and the Home Office could easily run definitive studies to confirm or disprove the outcome - if it wanted to.

But as Chai Patel, legal director at JCWI, told me: “The Government made no effort beyond the pilot to monitor the effects of the scheme. I think it's because they know they wouldn't like what they found.”

He highlights other examples - hospitals must now charge migrants for treatment, but no data is recorded on how much the extra admin costs the NHS, so it may well cost more than it saves.

Chai says JCWI collected its data deliberately to force the Judicial Review, and adds: “I think this is something that should be done much more, in different areas of policy”. I agree!

Thanks to Dave Whiteland for alerting me to this story!

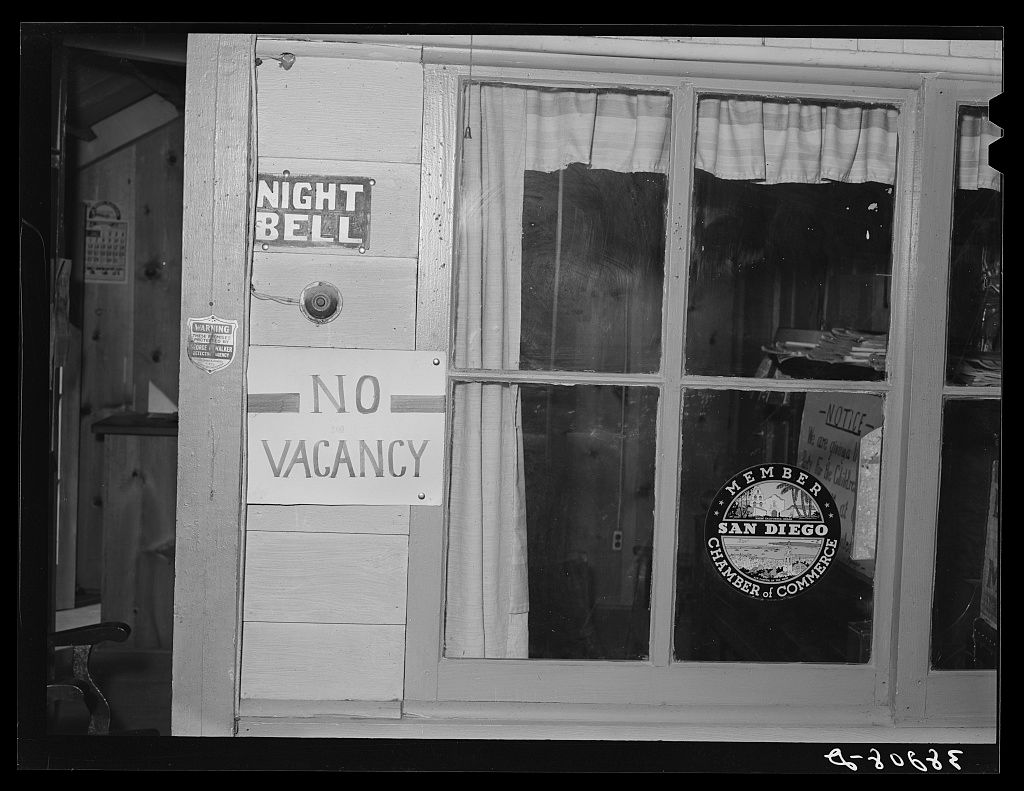

Photo credit: Library of Congress

I need your help

Thanks for reading! I’m keen to collect more ideas about important missing datasets, on any policy area in any part of the British state. If you’ve got any hints or tips, please drop me a line at anna@anna.ps, or tweet @darkgreener.