A truly massive missing number: where did £9 billion of quantitative easing go?

Since 2010, the vast majority of government spending has been public. UK local authorities must publish all spending over £500, and Whitehall departments must publish all spending over £25,000. The Government says boldly: "The public should be able to see where their money goes and what it delivers".

So I'm surprised to learn that another public body, the Bank of England, has recently bought corporate debt worth more than £9 billion, but never published details of its spending - without having a clear reason.

This seems like a strangely inconsistent transparency policy, not to mention a much larger gap in democratic oversight.

Background: the missing £9 billion

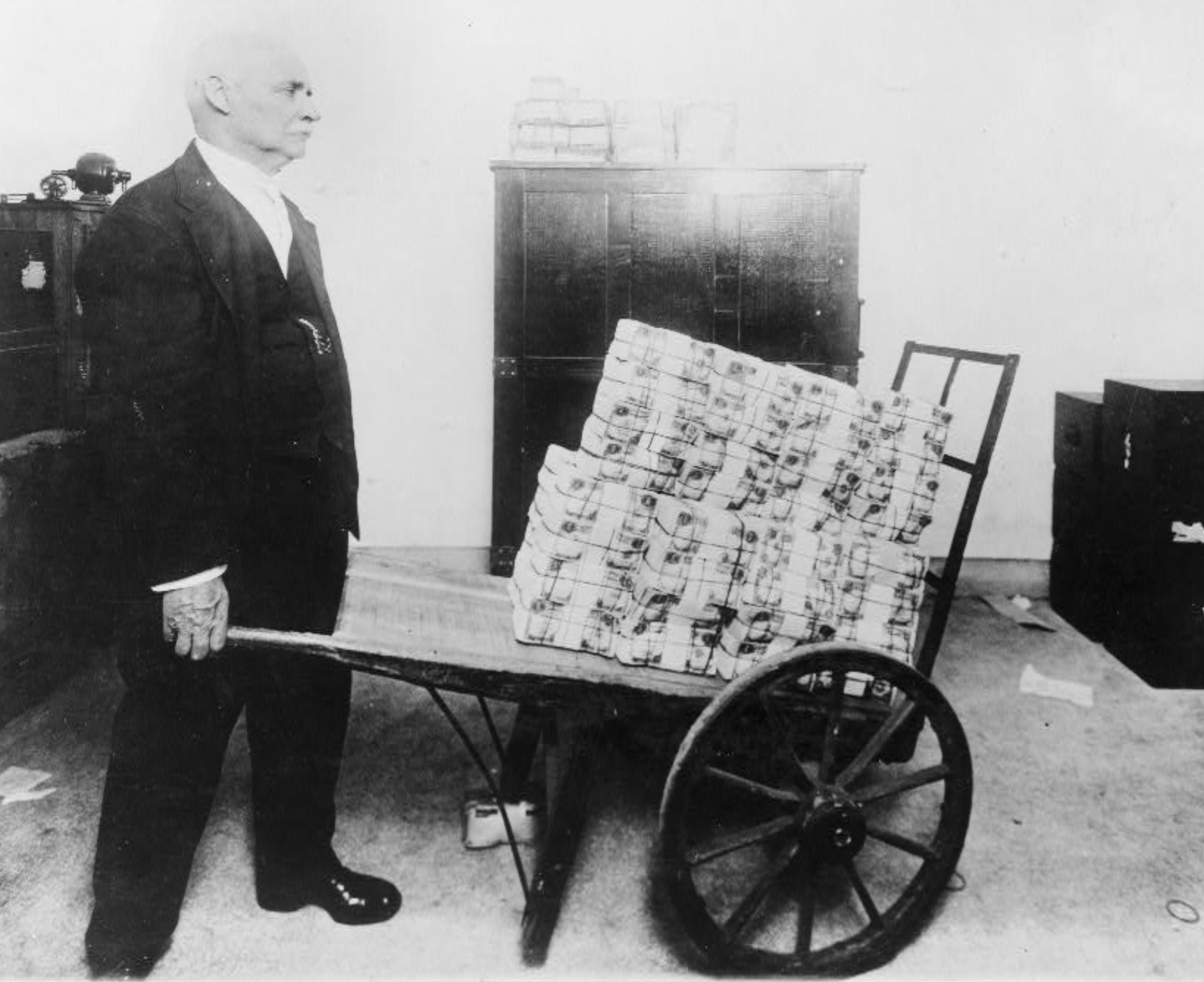

After the financial crash in 2008, the Bank of England began 'quantitative easing', buying up UK government debt to stimulate the economy. After Brexit in 2016, the Bank added corporate debt to the policy, hoping this would make it cheaper for companies to borrow and free up investors' cash for riskier assets.

Under the Corporate Bond Purchase Scheme, the Bank has splashed out on £9 billion of investment-grade sterling corporate debt. But where exactly did that £9 billion go: what does the Bank now own?

This is a missing number. We do not know.

I'll say that again, more slowly: even though we make local authorities publish truly microscopic spending decisions, we do not require the Bank to share spending decisions that are millions of times larger.

The Bank does publish a list (Excel) of the 144 companies that were eligible for the scheme - but not the amount of each company's debt actually purchased.

Why this data is missing

A Bank of England report on the scheme explains why it did not share purchasing decisions at the time:

It was thought that by disclosing less information, the Bank would reduce market distortions that might have arisen as a result of the publication of information on individual bond pricing and allocations. Moreover, it was thought possible that the publication of the prices paid in auctions might effectively render the Bank a price setter.

In short, the Bank feared distorting the market, which seems reasonable. However, since all the purchases under the scheme were complete by April 2017, the risk of market distortion is surely now long past.

So I asked the Bank if it would now publish details of its corporate debt holdings. But the Bank said it did not want to comment.

The problem with these missing numbers

This is probably just classic civil service caution from the Bank. But I think the decision not to publish should be debated more publicly.

This is for the following reasons:

- The list of eligible bonds includes the Daily Mail & General Trust. It seems like basic democratic oversight to know whether our central bank owns the debt of large media companies.

- The list also includes overseas companies, such as Apple, Wal-Mart and Deutsche Telekom, which "make a material contribution to the UK economy". But some of these companies compete with UK firms, and some have historically paid little UK tax. The nature of the "material contribution" should be discussed.

- The list also includes fossil fuel companies, like Shell and BP. As other parts of government divest from fossil fuels, we should have a public conversation about whether it's still appropriate for the Bank to hold these companies' debt.

- Governor Mark Carney has made public commitments to improve the Bank's transparency. This decision doesn't seem in line with the Bank's public position.

Things are better in Europe (slightly)

In 2017, MEPs asked the European Central Bank to improve the transparency of its equivalent corporate bond purchasing programme. The MEP Ramon Tremosa said:

A more transparent ECB will be stronger in its monetary policy. More transparency in the corporate debt purchases is fundamental to ensure that the single market and state aid rules are not undermined through the back door.

The ECB eventually complied, up to a point. The coupon and expiry date of each bond holding is in this Excel file, though not the total amount.

What should happen

Even if the BoE is justified in not sharing the data with the public, an issue with this level of democratic consequence needs democratic discussion. But this form of quantitative easing has never received significant attention in Parliament.

At the very least, a Parliamentary committee should be given access to the Bank's historic purchasing data, publicly debate the issue, and decide that no extra transparency is needed.

The Bank plans to restart reinvesting in corporate debt in the second half of 2019. So now is a good time to begin the debate.